Part 1. The Dream

Our story starts back in 2012.

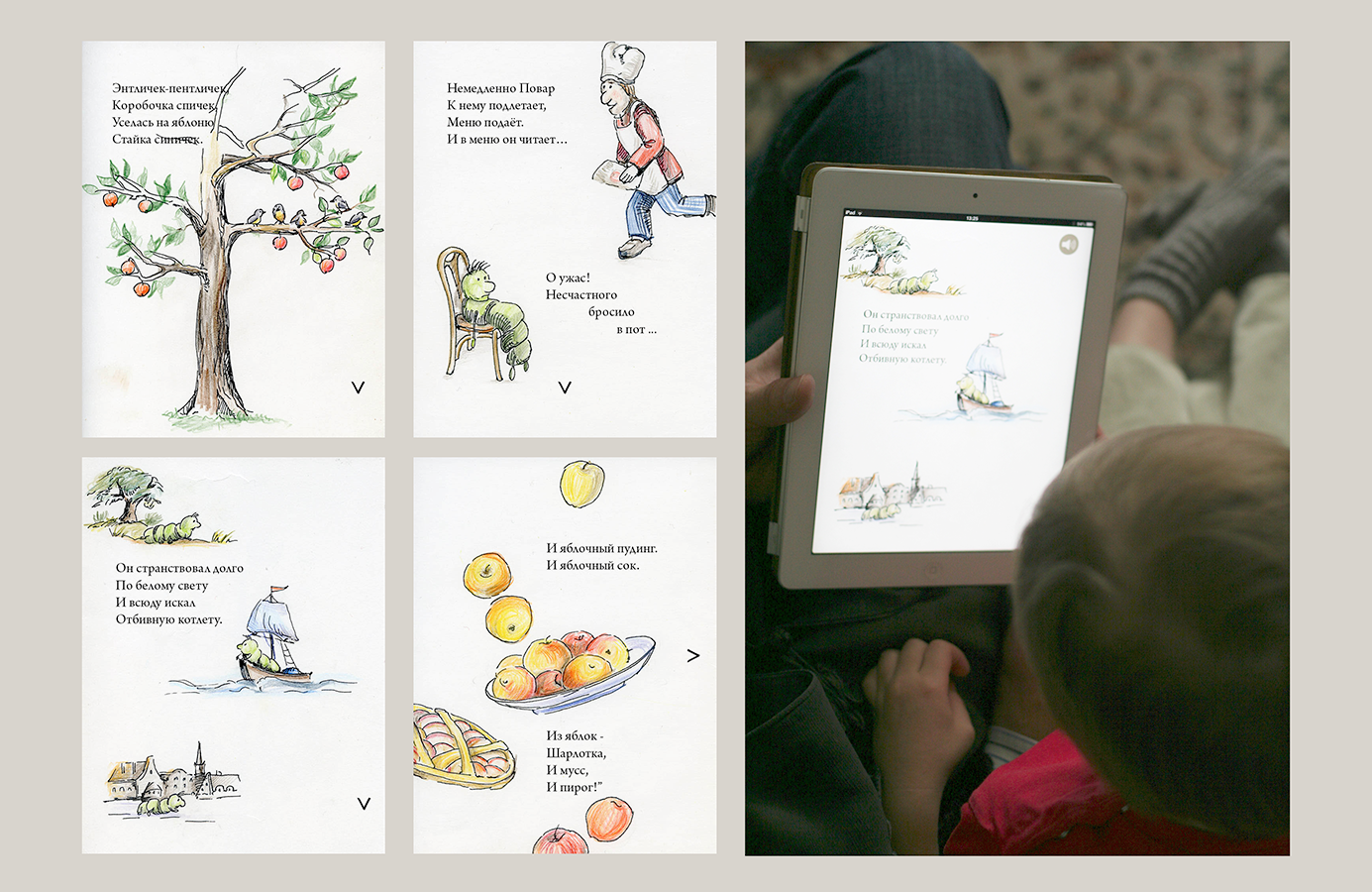

We started as a small collective of five people to work on one-off fairy tales for little kids, created by their parents on an iPad. Not Disney fairy tales, not a major App from App store, but parents' own Stories, packaged on their kids' iPads. One copy, personalized by those who know them the most at this precious age. So they would play not with a mass-market product but play with micro-myths created by their parents.

Then parents would start sharing some of those stories or games with other parents and their kids, and there would be a new grassroots movement of sharing myths horizontally instead of vertical distribution. We thought parents would spend their effort to build those micro-myths and apps, and many parents around us reacted to this enthusiastically and committed to doing just so.

But every fairy tale has a turn of events: Parents are busy. They have a day job. And while in theory dreams of creativity are widespread, the real grind of the creation process is damning. With all the tools we could have created back at the time, it was clear that it is not just simplicity that is lacking. It is the parents' energy to do so.

All the while we clearly saw that the idea of freeing their kids from the mass culture mono-myths is very exciting for many diligent parents. Many fathers who spend their days creating business empires are worried that they are missing something for the future of their kids.

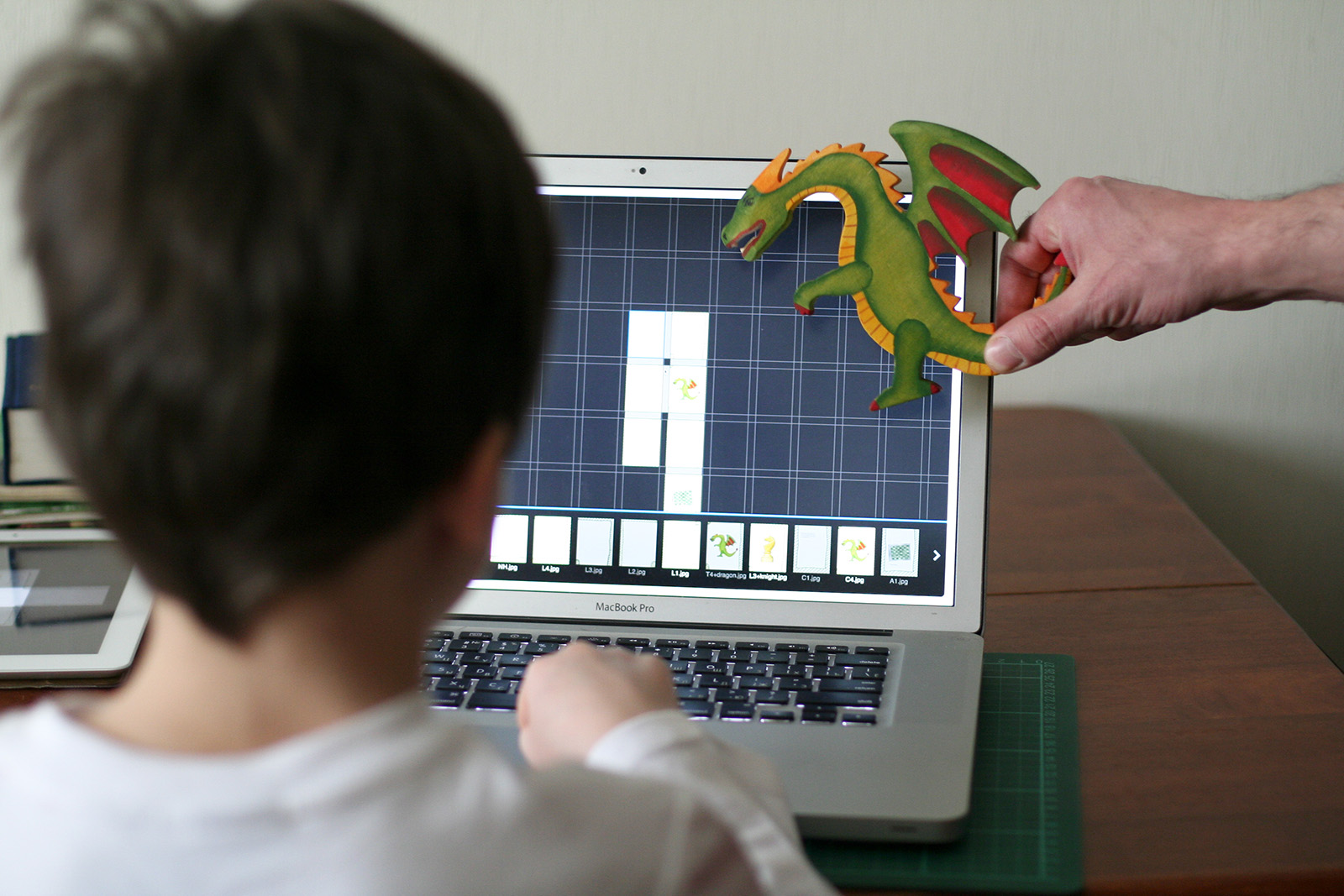

But we found an interesting thing: kids themselves have time. They have time and energy to create stories. Every kid wants to continue a story or create a new one. They are the only ones who can create stories easily without requiring advance payment on their royalties.

We as adults are so focused on making a living that the only creatures capable of creating something just for the fun of it are our kids. The rest of us are creators only as long as it is a byproduct of making money. There is a little bit of hyperbole in here, but a part of truth too.

So we got an idea of a StoryLeaf equivalent of Lego sets. So you start by going through the story first, in the form of a game or story book, and upon completion it falls apart into pieces (e.g. broken up by an evil witch), and from those pieces kids can reassemble their own story.

So we made this thing as a prototype, but it was very mechanistic. Very not alive. Because story blocks connecting with each other could not do this in a smooth way. There was simply no way back then to connect those story blocks without the pieces of glue visible. There was no way to continue the story in the given direction. Natural Language Processing existed back then but it was not within the reach of such a hobby project like ours. Even as ML algorithms started to proliferate in areas like efficient search or optimising news feeds for catching attention, the AI technology of the day was not capable of recombinating stories or continuing them with inventing storylines. This capability would have to wait until the arrival of a friendly wizard aunt with her Generative AI.

Part 2. The Second Coming

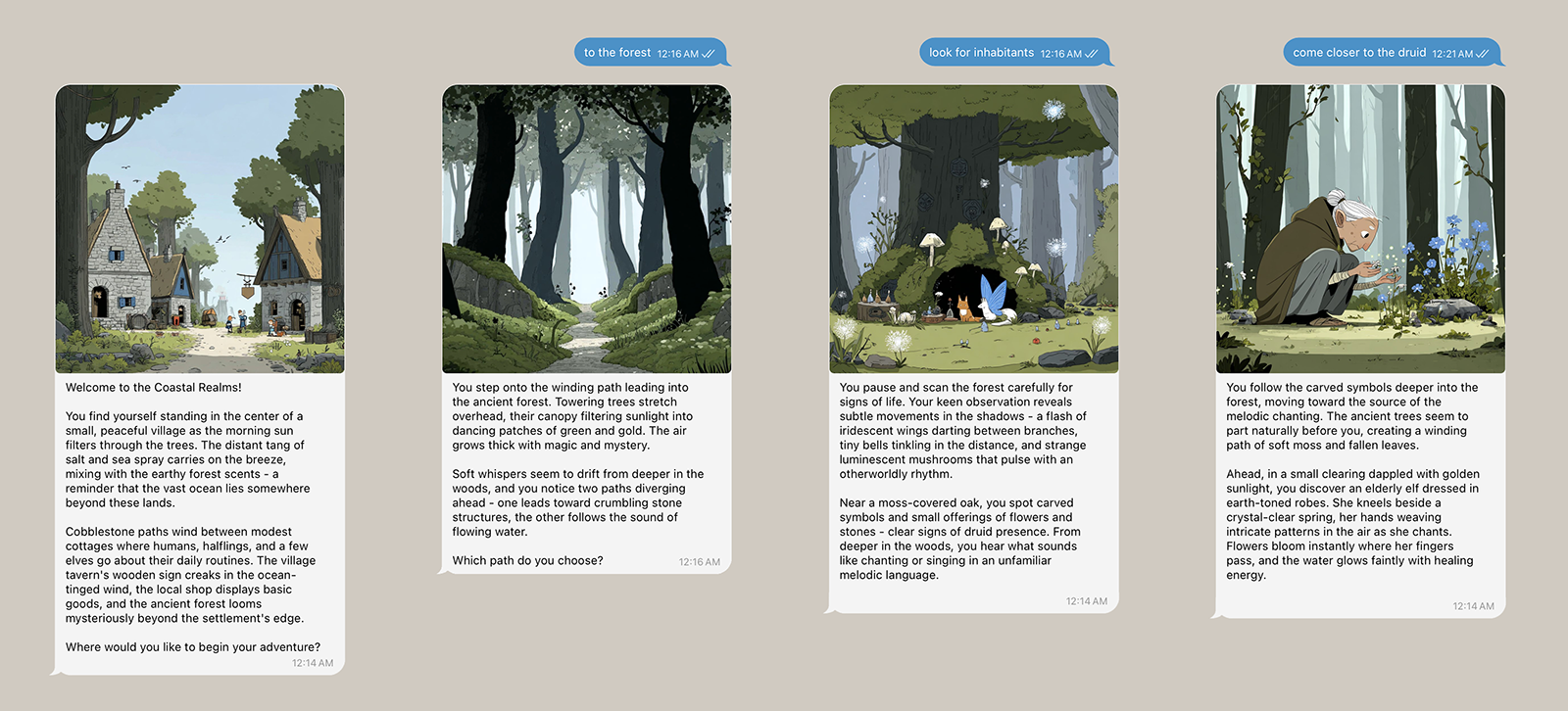

Let's step into the StoryLeaf experience…

You arrive at a village and it tells us about ocean breeze, and asks us where we would want to go. It shows us the picture of the surroundings.

There is a map behind this world, that describes locations, characters, events, and histories. But you don't know these stories yet. You're an explorer with your own interests, your own path to forge. Say you choose the forest, drawn to its shadows and secrets, and ask for its inhabitants. Suddenly pixies appear and you can start conversing with them.

This feels like those choose-your-adventure books from the 60s and 70s — and that's no accident. They inspired both our original 2012 StoryLeaf and the current rebirth. Back then, we even wove in fragments of Harry Harrison's Stainless Steel Rat series. Technically, those books were branching decision trees—brilliant but limited. They had maybe 30 branches, 50 if they were ambitious. Now imagine a tree with infinite branches, growing in real-time based on who you are. The pixies don't just offer you three dialogue options; they respond to your actual words.

Every child — every person — gets their own story, shaped by their choices, their words, their imagination. This isn't just personalization — it's recognition. Recognition that inside every user, whether they're 5 or 45, lives someone who wants to play, explore, and make believe. We're speaking to that part of you that still believes in magic.

And then, look, there are random encounters that are plot-driven. We suddenly find a map, and the moment of finding it is woven into the storytelling. The map reveals something about locations we can explore to learn more about this world. So that smell of the ocean from the first scene and the story the barkeeper told us become destinations we can visit to go deeper into this world.

Then there are all kinds of custom gameplay elements that a player can bring in. There's nothing better than being recognized for your inner idiosyncrasies. For example, I can mention that I'm trying to invent haikus describing current situations, and just after a couple of turns like that, it will generate in-character haikus for my character on every turn. The game doesn't just tolerate your quirks — it amplifies them into art.

So who is this for? Anyone with the heart of a fanfic reader or writer — which is to say, anyone who's ever wanted to live inside a story. We're creating different settings for different ages: young adults, kids, and even toddlers from 2.5 years old.

We hope to create an alternative to YouTube videos for kids. Perhaps we'll introduce movement later, but there's something powerful in stillness. Those of us who grew up with filmstrips and illustrated fairy tales know this truth: when images don't move for you, your imagination moves through them. This is where the voiceover becomes essential—warm, knowing, alive with personality. It carries the DNA of old radio plays, painting worlds with voice and sound while your mind animates the rest.

The illustrations need a consistent style — think of how you can always recognize a Miyazaki film or a Beatrix Potter tale. Not by photorealism, but by voice. Each image starts with our Imaginary Illustrator — an AI agent that translates story moments into rich visual descriptions. It's opinionated, interpretive, even subversive sometimes. This is what human illustrators have always done — added layers, suggested moods, revealed character through color and composition. Except now it's one-off, creating a unique visual language for each player's journey.

Which brings us to the heart of it: We want to hand children the tools of creation. But let's be honest — "children" is just another word for humans. We all exist on this spectrum: at one end, our LinkedIn-polished slaves, following protocols to pay the bills. At the other end, what we really are — creation machines who can't stop extruding stories, building worlds, playing god with pixels and words. We tell stories because that's the only thing humans truly want to do.

None of this is new — and that's exactly the point. Maria Montessori figured it out: create the right environment, then get out of the way. Let children explore freely in a space designed for their success. It worked for Sergey Brin and Larry Page. Gianni Rodari went further, teaching Italian kids that fantasy has grammar, that imagination follows patterns you can learn and play with. His summer camps were story laboratories. Now we have the technology to build Montessori's environment with Rodari's creative tools inside.

One more thing. This is not about technological utopian futures. It's not about the happy ending of flying to Mars and having a new life there. This is about how to take human civilization and culture and wrap it up in an environment for creating the world that is best for you or your kids.

The technology is just the bottle. The culture is the message. The imagination is everything.